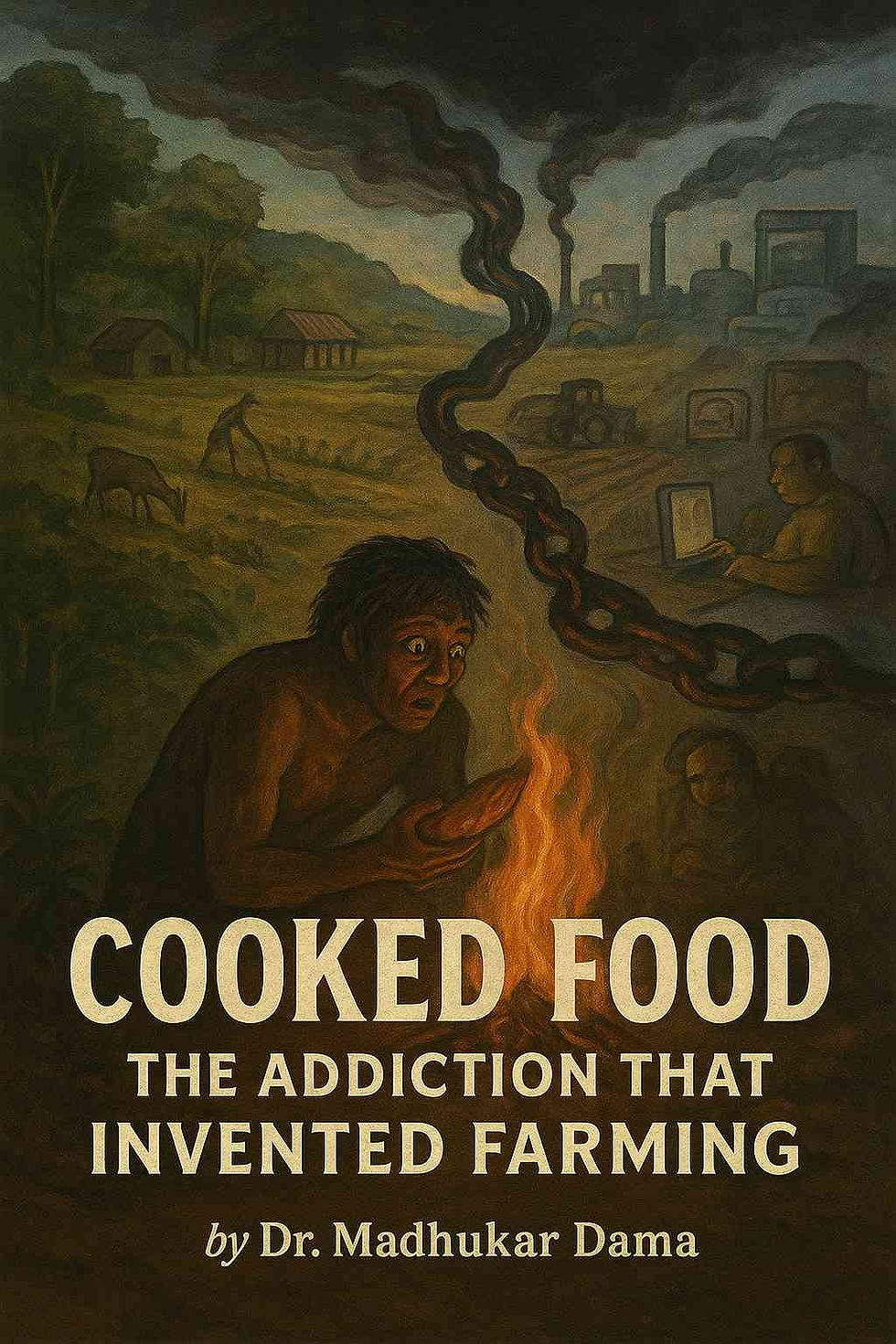

Cooked Food: The Addiction That Invented Farming

- Madhukar Dama

- Aug 30, 2025

- 8 min read

Human beings like to believe we are rational planners, shaping history by deliberate choice. We tell ourselves that farming was a conscious invention, a great leap forward, the foundation of civilization. But the truth is subtler, deeper, and more unsettling. Farming did not create cooked food. Cooked food created farming. Or more precisely: the addiction to cooked food created farming, and it drives it still.

This is not just a play of words. It is a reversal of the official story of civilization. To understand it, we must follow the trail of fire, hunger, habit, and desire across history and into our present moment.

---

The First Fire: Birth of a New Hunger

For millions of years, humans lived as gatherers and hunters. They ate what the land provided — fruits, nuts, roots, leaves, insects, small prey. Their bodies, like all creatures, were tuned to the rhythms of raw abundance. Then came fire.

Fire gave warmth and protection, yes. But when roots and meat were accidentally dropped into flames, something happened. The smell, the softness, the sweetness of cooked starch or roasted flesh was not just food — it was a new stimulation of the senses. Heat unlocked calories faster, melted textures, and released narcotic comfort. The tongue rejoiced, the belly sighed, and the brain lit up with pleasure.

In that moment, a new hunger was born. A hunger not for survival alone, but for that particular altered state of food. A hunger that no raw tuber or wild fruit could match. Humanity discovered not just nourishment but intoxication.

Cooked food became the first drug.

---

Addiction Becomes Culture

Once the body and brain learned this trick, there was no turning back. The more cooked food people ate, the more they preferred it. Children raised on it rejected rawness. Families gathered around fire not just to warm themselves, but to feed their growing dependence.

This was not a neutral development. Cooked food dulled certain instincts and heightened others. It made food softer, so teeth and jaws weakened over generations. It altered digestion, making guts shorter and dependent on external heat. It created an expectation: that food must be softened, flavored, transformed. In short, humans adapted not just biologically but psychologically to this addiction.

Addiction always seeks security. The craving for cooked food required regular supplies of roots, seeds, and animals. But wild landscapes were uncertain. The tubers could run out. The animals could flee. The fruits were seasonal. Fire and craving demanded constancy.

And so, instead of waiting on nature, humans turned to bending nature. Farming was born.

---

Farming: Servant of the Cooked Tongue

It is often taught that agriculture arose for efficiency, for surplus, for progress. But beneath these explanations lies a simpler truth: cooked food could not be sustained without farming.

Consider grains. Wheat, rice, barley, maize — none of these are pleasant to eat raw in bulk. They are too hard, too dry, too bitter. Only fire transforms them into bread, porridge, rice bowls, and chapatis. These crops are the perfect partner for cooking, but almost useless without it. Farming them only makes sense in a cooked culture.

So it was not farming that gave us cooking. It was cooking that demanded farming — especially grain farming. Humanity became enslaved to starchy harvests because they were the most efficient raw material for fire-based food.

Thus, farming expanded not as a neutral technology but as the plantation of addiction.

---

Civilization: The Empire of the Stove

From the earliest settlements in Mesopotamia to the granaries of the Indus Valley, from the rice paddies of China to the maize fields of Mesoamerica, the story repeats: farming supported cooking, and cooking demanded farming. Villages became cities not out of abstract progress, but because cooking required fuel, utensils, storage, and continuous harvest.

The stove became the hidden altar of civilization. Around it clustered kinship, rituals, festivals, and economies. Taxes were measured in grain, armies marched on bread, empires rose on rice. The addiction was not individual anymore — it was institutionalized.

Priests sanctified offerings of cooked rice. Kings built granaries. Traders moved salt, oil, and spices to flavor the fire-born meals. Entire forests were felled to supply firewood. All of this because once humanity tasted cooked food, it could not imagine returning to the raw freedom of earlier life.

---

Philosophical Mirror: Who is the Master?

Here lies the paradox. We believe we control food, but in truth food controls us. Or rather, our altered relationship with food — our addiction — controls us.

This addiction shaped not only agriculture but morality. Fasting, feasting, purity, pollution — all tied to cooked food. Cooked meals marked identity: who one eats with, what is acceptable to cook, what fire is sacred. Communities and castes were defined not just by belief but by cuisine.

In India, the daily cooked meal is not merely food, it is dharma. To refuse it is to reject society. Yet behind this sacredness hides compulsion. The addiction cloaked itself in culture, so no one would question it.

Philosophers may debate free will, but what is freer than a body forced by habit to demand heat and spice at fixed hours? The stove rules stronger than kings.

---

The Modern Machine: Addiction at Industrial Scale

Fast forward to today. The ancient fire has become the modern kitchen, the global food industry, the chemical laboratory of flavors. Cooking no longer stops at firewood or frying — it stretches into processed foods, preservatives, and industrial additives. The same principle remains: alter food, excite senses, bind humans deeper.

Farming too has swollen into industrial agriculture — monocultures of wheat, rice, corn, soy. Forests fall, rivers dry, soils die, but the addiction remains unchallenged. Billions are kept alive, not by raw nature, but by the continuous supply chain of cooked food ingredients.

Obesity, diabetes, heart disease, cancer — these are not random plagues. They are symptoms of a species that mistook its addiction for nourishment, its craving for progress.

---

A Timeless Truth

Strip away the pride of civilization, and what remains? A species that discovered a drug in fire, grew dependent, and reorganized the planet to feed its habit. Farming did not create cooked food. Cooked food created farming. And it still drives it.

Every new agricultural development — from tractors to GMOs, from irrigation to fertilizers — is not for “feeding the world,” but for sustaining the stove. Civilization itself is nothing but the scaffolding of a cooking addiction.

---

Epilogue: Freedom or Fire?

The question then is not historical but existential. If addiction created farming and civilization, can there ever be liberation? Can humans live without cooked food, without farming, without the endless expansion of this system?

Perhaps not easily. The body is reshaped, the palate conditioned, the culture woven deep. Yet awareness matters. To see addiction as addiction is the first freedom.

We may never go back to the forests, but we can understand that what we call “progress” is in fact a long dependence on fire’s narcotic gift. Farming is not our invention — it is the invention of our cravings. And until we see this clearly, we remain not farmers of the earth, but servants of the stove.

---

🔥 Thus, cooked food is not merely a meal — it is history’s greatest addiction, the silent force that birthed farming, sustains civilization, and continues to shape the fate of humanity.

A Night of Fire and Farming

(A Slow-Burn Dialogue at Yelmadagi)

It was dusk at Yelmadagi. The sky turned copper, and the air smelled of damp earth and smoke from a small fire Madhukar had lit near his homestead. His house stood modest, built of stone and clay, off-grid, surrounded by patches of millet and wild shrubs. Chickens dozed on branches, and somewhere in the distance a cow lowed.

The fire crackled, and around it sat four figures:

Madhukar, host, thinker, provocateur.

The Philosopher, cloaked in quiet reflection, quoting ancient wisdom.

The Historian, sharp-eyed, carrying centuries in his memory.

The Agricultural Scientist, practical, skeptical, yet open.

They sat cross-legged on mats. As the flames licked upward, so did their thoughts.

---

The Spark

Madhukar:

“Everyone says farming gave us civilization. But what if it’s the other way? What if farming itself is just the servant of cooked food? What if cooked food — the addiction — invented farming?”

The fire hissed as if in agreement.

---

The Philosopher Speaks

Philosopher:

“You touch the essence of inversion. We believe man controls fire, yet perhaps fire controls man. Plato once warned that desire, once tasted, makes us prisoners. Cooked food is not mere sustenance — it is pleasure transfigured, an altered state. Once humans grew accustomed, they could not return. The philosopher in me sees not progress, but dependence disguised as progress.”

---

The Historian Interjects

Historian:

“Archaeology supports this. Consider grains — wheat, rice, maize. They are harsh, bitter, almost inedible raw. Yet with fire they became the foundation of empires. Why would people choose such crops unless cooking bound them? Look at the Indus Valley: vast granaries, centralized storage, taxation in grain. Not because they loved farming — but because they could not live without cooked grain. Civilization was built on a stove, not a plough.”

---

The Agricultural Scientist Counters

Scientist:

“Addiction, you say. But isn’t cooked food also adaptation? Heat kills pathogens, unlocks calories, makes digestion efficient. Farming answered that need — reliable harvest for reliable cooking. To me, that is survival strategy, not just craving.”

---

Madhukar’s Reply

Madhukar:

“Survival? Or dependency? If cooked food is adaptation, it’s the adaptation of an addict. Look around: soils dying under chemicals, rivers drained for rice, forests cut for wheat. If farming was born from addiction, then everything since is escalation. Just like a drunkard needs more drink, humanity needed more farmland, more yield, more chemicals, more machines. Survival has become servitude.”

---

Slow-Burn Reflections

The fire dimmed and shadows thickened. The forest’s chorus swelled: cicadas, crickets, owls. The talk deepened.

Philosopher:

“All addictions justify themselves as necessity. The body forgets what freedom felt like. So too mankind: once raw food sustained us, now we call it primitive. Yet what is primitive — raw fruit, or chemical bread?”

Historian:

“Consider too the rituals. In India, rice is sacred, chapati daily dharma. But beneath sanctity hides compulsion. The historian in me says: our gods are born from our hungers. Priests bless cooked grains because society cannot bless abstinence from them.”

Scientist:

“But you cannot deny the resilience. Cooked food allowed dense populations, specialization, science, art. Would we even be sitting here discussing this without it?”

Madhukar:

“Yes, but at what cost? You see progress; I see slavery. Forest peoples still live free on fruits, roots, leaves. Civilization calls them backward. But who is backward — the man who eats what nature gives, or the man who burns the earth to cook his cravings?”

---

Toward Midnight

The flames dwindled, glowing embers now. Each thinker gazed into them, as if the fire itself was the hidden guest of the gathering.

Philosopher:

“Addiction dressed as culture. Survival dressed as progress. We must peel words to see truth.”

Historian:

“History is written as triumph. But beneath it lies compulsion.”

Scientist:

“Science too has been servant to hunger, not master of it.”

Madhukar:

“Exactly. Farming did not create cooked food. Cooked food addictions created farming. And they drive it forever. Until we see this, we remain not farmers of the soil, but slaves of the stove.”

Silence followed. Above, stars spread in unpolluted clarity. The night held them in its vastness, and the embers whispered what words could not.

---

✨ Thus ended the Yelmadagi discussion: not with answers, but with fire still burning — in the hearth, in the mind, in the belly of civilization itself.